We all remember those Apple ads, right? The ones featuring images of instantly recognizable leaders from all places of the world, involved in all manners of professional fields. There were Mahatma Gandhi, Eleanor Roosevelt, Amelia Earheart, Miles Davis, Pablo Picasso, and, of course, Steve Jobs, all featured alongside the words: Think Different.

This ad campaign was a wildly successful one, and was defining for Apple, specifically in its ability to put forth a strong brand identity for the company, one which still exists, decades after the campaign first ran. Apple created this identity in order to align itself with genius, creativity, and originality. The people who used Apple were icons, yes, but they were also iconoclasts. They broke the mold and often refashioned it in their own image. They embodied the idea of thinking differently as the only true path to brilliance.

The irony of these ads, of course, is that their widespread success has meant that Apple’s popularity surged. More and more people bought their products, wanting to identify with a brand that explicitly advocated thinking differently. Meanwhile, what Apple was implicitly saying was: “Think like everybody else and buy our products and never stop buying them and have some freaking loyalty to a corporation why don’t you.”

We like to think we value the iconoclast, the rogue, the maverick. When it comes right down to it, though, we pretty much all fall prey to the comforts of group think.

But so, the point here isn’t really about Apple, even if it also kind of is. Rather the point here is that as a culture, we merely pay lip service to the idea of thinking differently. We like to think we value the iconoclast, the rogue, the maverick. When it comes right down to it, though, we pretty much all fall prey to the comforts of group think. Never is this more true when it comes to raising children.

Which, look: I get it—especially when it comes to kids. It’s easier to want them to be typical in their development. We want our kids’ lives to have the “right” kind of challenges. We don’t want the kinds that will lead to bullying, or to frustrated teachers. This is an understandable impulse, as a parent, but it is also an untenable one. This is especially true when you are raising a child who undeniably has a different way of thinking. These kids cannot necessarily be expected to comfortably exist in the mainstream, let alone to thrive.

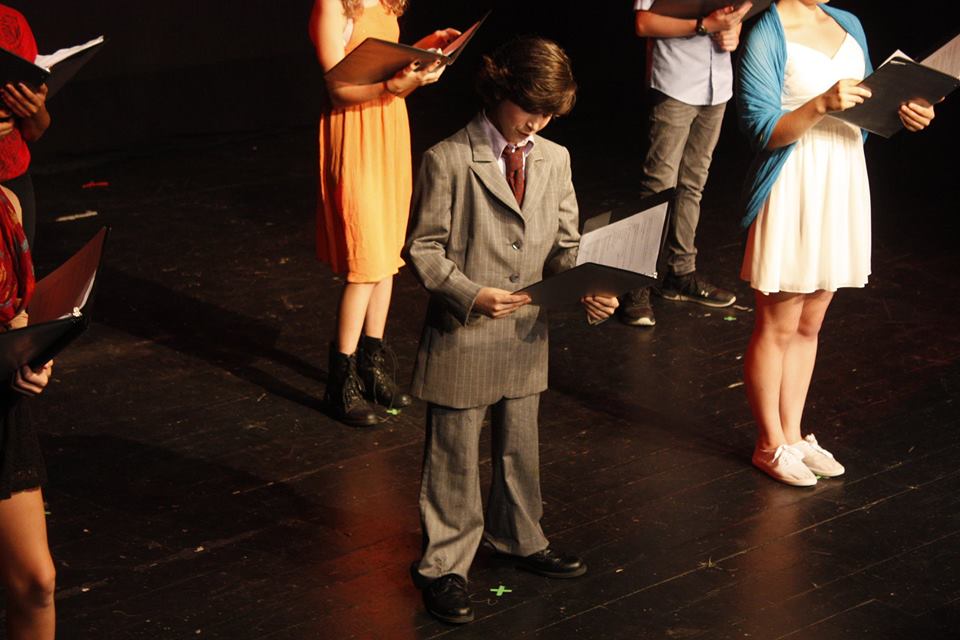

First, what does it mean to think different? One simple way of realizing that your child thinks differently is if they learn differently. This might be apparent from an early age, when a teacher calls out a child for being disruptive during circle time. “Disruptive” can mean that they don’t want to sit in one place for 20 minutes at a time. “Disruptive” could also mean that they constantly ask “why” when their teacher offers seemingly arbitrary reasons for why things need to be a certain way. Rebelliousness is a key signifier of a different thinker, but its presence in young children often leads to frustration on the part of teachers—and parents.

And, in fact, here’s where parents need to step in and help their differently thinking child. The best and probably easiest way of doing this is by allowing kids to express feelings of dissent. If your child says that something is unfair or wrong, listen to them. Don’t do the knee-jerk thing so many parents do and side with the person in authority. (Even when that person in authority is… you.) Instead, help your child to figure out a way to solve their problems for themselves. Remind them that veering off from the expected path doesn’t mean they’re taking a wrong turn, it just means they’re finding a new route.

It’s really easy for adults to obsess over culturally approved success markers.

This might also be an important thing to remind yourself, as the parent. It’s really easy for adults to obsess over culturally approved success markers. Think: the right neighborhood to live in, the right job, the right salary, the right schools for your kids. But we must stop that. In part, because it’s a bad example to set for our kids. But also because it’s not an ideal way to live our own lives.

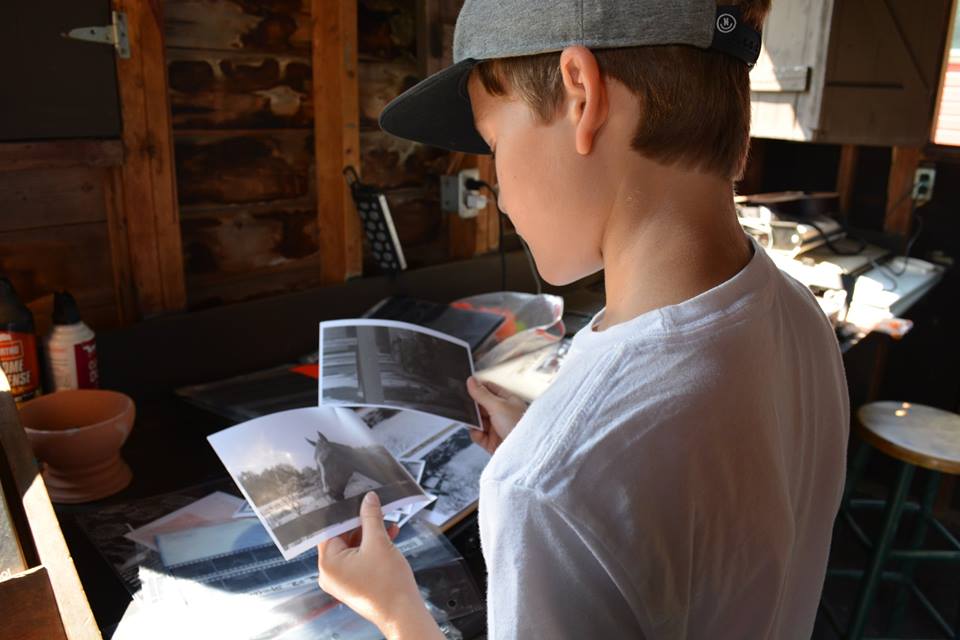

Ways in which we can help our kids—both those who naturally are different thinkers, and those who should be encouraged to stray from the norm—include giving them more responsibility. By doing things like allowing kids agency in planning their schedules, we are offering them the chance to turn frustrations into creative solutions. We should also think carefully about the environments in which our kids exist. Some different thinkers can thrive even in traditional settings. Once encouraged to utilize their inquisitive nature in beneficial ways, they can adapt to their surroundings. Not every differently thinking kid is like that, though. As parents, we need to make sure that our kids are in situations where different thinking is accepted and encouraged.

What we must remember is that being a different thinker doesn’t mean being an outcast. Even when encouraging our kids to find their own paths to success (whatever shape “success” takes), we must remind them that respecting others can lead to worthwhile collaborations and experiences. Rules can be bent and even dismantled without leading to chaos. And, in fact, different thinkers often do well with having some rules in place, even if they are simultaneously encouraged to use those rules as a guideline instead of an ironclad system.

The biggest thing to remember when raising a kid to think differently is to be open to doing the same yourself. There is no right or wrong way to live a life. And whether or not your child is the next Steve Jobs is beside the point. Rather, the point is to allow your kids the freedom of figuring out who they want to be, not who others are telling them they ought to be. And that’s where true originality can be found—and it has nothing to do with what kind of laptop you use.