When my kids were little, a screen-free upbringing (or, at least, screen-limited) was incredibly important to me. They so rarely watched television and so rarely saw me watching television that I vividly remember the first time my older son saw a commercial on TV; he was four years old and after watching a string of ads in the middle of a cartoon show, he turned to me and asked: “How did we ever know what to buy without watching these?”

I’ve repeated that anecdote for a dozen years now, always enjoying my son’s precocious observation, as well as the implication that he was never exposed to anything so mundane as regular TV. As do many parents, I sometimes veer toward being straight up obnoxious. (What? It masks other deep-rooted insecurities! Anyway.)

It’s funny, now, because any smugness I used to feel about not being a parent who parked their child in front of a show whenever they needed 15 minutes to take a shower has long since vanished. However, the screens to which my 16- and 13-year-old sons are most attached are not televisions, but rather those of their phones. Like just about all people not only of their generation, but also of any generation alive today, my kids are more likely to be found without their, I don’t know, literal arms than their phones.

Any smugness I used to feel about not being a parent who parked their child in front of a show whenever they needed 15 minutes to take a shower has long since vanished

I suppose it all started innocently enough, with regular flip phones purchased once they came of an age to walk to school alone. I’m far from a helicopter parent, but I did want text message-confirmation that my kids had made it the few blocks away to school safely. Soon enough, those flip phones graduated into smart phones and it felt like, overnight, all the work I’d done over the years—the limited time spent watching television, the refusal to buy video game systems, the insistence upon reading books and listening to music on car rides—had vanished in an instant. It was… disheartening, to say the least.

And yet, it was hard for me to be altogether that surprised. After all, I too had a smart phone and a near compulsive habit of looking at it throughout the day. And too harshly limiting the time they spent on their phones felt Sisyphean; their phones were their way of connecting to their friends and the outside world, of gathering news, and, yes, playing games. Sure, I could ask them to put their phones away when I was around them—and they would listen—but I’m not around them all the time, and I’d be a fool to think the phones didn’t come back out once I was gone.

Further complicating this phone- and social media-addicted reality is the fact that, as mentioned before, I fall prey to it as well. And I relate to why they succumb to their phones: They view them as an escape, as relaxation time, a way to unwind after the rigors of their school days and homework sessions.

It’s an ironic aspect of our reality that the way in which so many of us choose to disconnect from the rest of our lives is by connecting to our screens

But, of course, it’s not that simple. While, yes, it can feel like a specific type of mental zoning out to just text with friends, or scroll mindlessly through our Instagram feeds, there is nothing inherently relaxing about being attached to a screen. On the contrary, phones—and everything they represent—are stimulants; the constant stream of information keeps us on edge—and craving more and more. It’s an ironic aspect of our reality that the way in which so many of us choose to disconnect from the rest of our lives is by connecting to our screens. But it’s a hard habit to break, one whose only cure can seem to be going cold turkey. Easier said than done though, right?

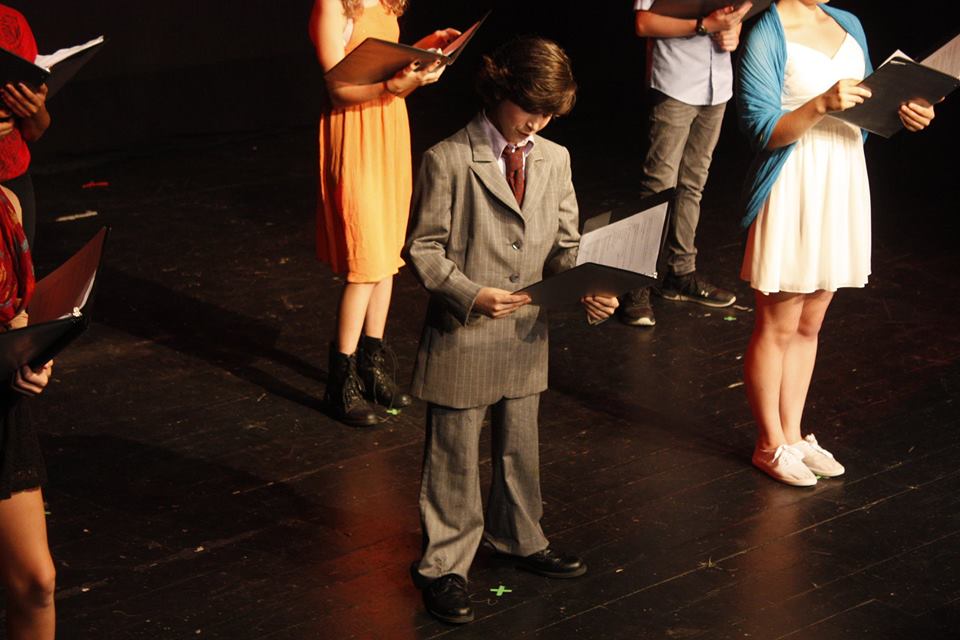

And yet: There is one surefire way of achieving a true disconnect—at least, one that I found for my sons. And that’s their time in camp. While some camps don’t have a strict no-phones policy (often enough it’s because parents just can’t handle not being in touch with their children!), Ballibay does—and I can’t help but think that this is one of the reasons my children look forward to their summer weeks there so much.

Since they can’t use their phones, my kids don’t even bring them; there’s absolutely no temptation to use them at all. Instead, they spend their time engaged with the people and activities around them. One of the things I most love about Ballibay’s philosophy is how camper-led it is, by which I mean that it’s the kids who figure out what it is they want to do and when to do it, and go from there. This leads to a true feeling of agency for the campers, something which I think is missing when they find their free time being occupied by the siren calls of social media. There’s no choice attached to using your phone, is the thing; it feels like an inescapable situation, like the addiction it is. At Ballibay, without their phones, kids get to experience what it’s really like to make a choice about what it is they want to be doing.

I’ve thought often about the many times I would, as a child, either think to myself or say out loud, I’m bored, and how my own kids rarely ever do that—they always have something to occupy them, and it happens to be their phones. But boredom is not a bad thing, because it takes ingenuity and creativity to solve this problem. If a phone and all its bells and whistles can answer the question of what to do all the time, we eventually won’t have the ability to do so ourselves—we’ll be letting apps answer that question for us.

This is all the more reason it’s important to divest our kids of their phones on occasion. At Ballibay, they spend weeks without them, and, as per my kids, they don’t even miss them. So the real question is, how do we maintain that, as parents, during the camp off-season?

For me, the answer to that begins with my own phone use. I’ve made the conscious choice not to look at my phone as much around my kids, or during time when I would’ve mindlessly used it, like on my daily subway commutes. Demonstrating to my kids that I’m exercising my option to pull out a book to read, or a notebook to jot down thoughts, or even nothing at all, and am just allowing my mind to wander where it wants to go, has been, I think (I hope!), a powerful thing for them to witness. Then, too, I have put into place stricter rules about when they can and can’t use their phones at home. And when they’ve complained, it’s been simple enough to remind them of how long they went without phones at Ballibay, and how much they enjoyed their time there.

The importance of having separation from screens can’t be overemphasized. Not being with a phone teaches kids—and adults—a level of resourcefulness that we’ve grown complacent about. It teaches us all to be more creative, to interact in the old-fashioned, analog way (you know, face-to-face communication!), and it serves as an important reminder that our phones and social media presences belong to us, but we do not belong to them. The power is within us, and it’s beneficial to unplug once in a while—or even more than that.