There’s a parenting trope centered around careers with which I’m sure you’re all familiar. Basically, it relies on the presumption that it’s incredibly important where your child goes to preschool, because this will lead to going to the “right” elementary school, and the “right” middle school, and the “right” high school, and the “right” college, which will, of course, land your child the “right” job, where he or she will, presumably, make the “right” amount of money, i.e. a lot.

Are you exhausted just reading all that? I sure am. I’m also well aware of what’s missing in that whole ladder to… success. Namely: any indication of what the children in question might want for themselves. This type of parenting doesn’t focus on what’s right for the child. Rather, this type of parenting focuses on what society has determined to be “right” according to a very stringent set of limitations. It’s a reductive and boring way of looking at the world—and at your child’s future. Unfortunately, it’s also a very common one.

There’s no doubt that even well-meaning parents fall into this trap. Even if you aren’t the kind of parent who thinks that school—and really all of childhood, including extracurricular activities and pursuits—are just steps taken on the way to something bigger, more important, it’s still possible to lose sight of the present and look toward the future. Or, alternately, it’s possible to see what’s happening in the present and think of it only in terms of the future.

Capitalism encourages us to think about our love in terms of its utility.

Like, seeing how your child loves to take toys apart and think to yourself that this means they will be an engineer. Or, taking your kid’s love of the subway system as a sign that they will grow up to be a city planner. It’s easy to do this because we are preconditioned to do this. Capitalism encourages us to think about our love in terms of its utility. And so of course we, as parents, try and figure out what our kids like. And then we encourage them to explore those things further. It’s practically a capitalist mandate! Ugh.

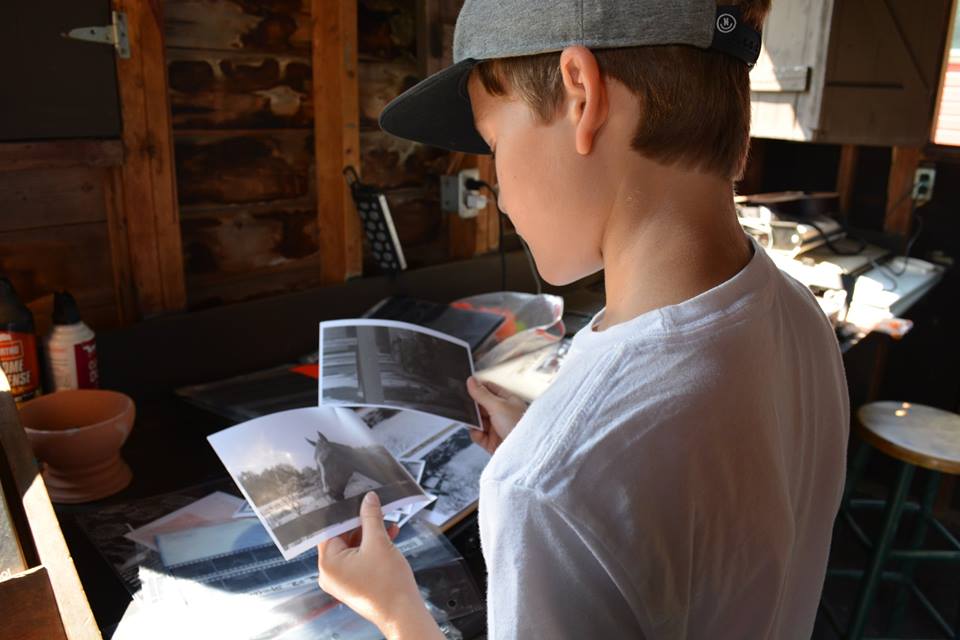

But it doesn’t have to be this way. First, parents should always try and do a better job at getting out of the way of our kids. We shouldn’t be figuring out what they like. That should be something self-directed by the kids. This is one of the things at which Ballibay excels. The camp allows kids to figure out for themselves what they love to do. And rather than focus on an end goal for those interests, or encouraging kids to get involved only with those activities at which they are innately talented, Ballibay does the opposite. It’s a process-oriented camp which encourages experimentation. So, even though my children entered camp with a general idea of the areas which interested them, they wound up being drawn to different pursuits and experiences.

This isn’t to say, however, that parents should sit back and see what their kids are naturally interested in and then build an education and career plan around that. Not at all! The thing is, parents need to start actively resisting thinking this way. There is simply no need to be career planning for kids who aren’t even in college yet. Nor is there even a real reason to do this when they are in college.

We are conditioned to think that living to work, rather than working to live, is a normal way of being.

We are conditioned to think that a career is what will bring us personal fulfillment. We are conditioned to think that through our jobs we will find stability. We are conditioned to think that living to work, rather than working to live, is a normal way of being. We are conditioned to think that the answer to the question “what do you do?” will tell us not what a person’s job is, but rather who a person is.

We are conditioned to think these things, but we should break that conditioning with our kids. We should instead be teaching them (and hopefully also by example) that their interests do not have to result in something professional, or even professional-adjacent. It is all too easy these days for people to think that everything they do must result in something lucrative. This is one of the many dark sides of the rise of the “gig economy,” a Silicon Valley creation that leads people to think they must always be hustling, always be earning. It is insidious psychologically, and also has negative ramifications (i.e. the degradation of unions and other important workers’ rights organizations) that extend beyond just the “all work and no play” mentality it promotes.

Instead of seeing our children’s interests as harbingers of their professional futures, we must resist that impulse, and instead see their interests as merely that. We should encourage our children to pursue those things that they love, and to do so just because of that love. This is important also because of the fact that so many traditionally stable industries are in states of flux as our world changes dramatically. Scary as that is, this notion that traditional paths to professional success are now dead ends, it could also be liberating, and a chance to rid ourselves of ideas of what success looks like at all. We should, anyway, allow our kids to define what success means to them, and let them lead themselves down their own paths.

Certainly one way of doing this is offering them a few weeks every summer at a place like Ballibay, a place where they won’t be assessed and graded and told what they’re “good” at and what they’re “bad” at and what that means for their future. Instead, they’ll get to be in an environment where they can just be. Maybe they will find something that, one day, they’ll look back upon and see as a sign of what their future would hold. Or maybe they won’t. No matter what happens, though, we as parents should be encouraging them to live in the moment, not in some distant future filled with job applications and invites to connect on LinkedIn. These are our children. They deserve better than that. And so do we.